El Texano

Profile

| El Texano | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biography

by Steve Sims

Adios á un Cachanilla

"the people in Baja (California) Norte are called Cachanillas. Cachanilla is a desert plant and it has to be tough to survive. Once a year, after the rains, a single flower blooms, and it's a beautiful flower.'

"He is a local, a cachanilla (minimum fifth-generation Baja Californian).'

Lucha libre legend 'El Texano' passed away Monday morning, January 16, 2006, en route to a hospital in a southern suburb of Mexico City, not in Guadalajara as had originally been thought. Three separate published reports listed three different times; one had 1:00 AM early Monday morning, one had 2:00 AM, and one had 4:00 AM as the time of death. He died of respiratory failure (the proximate cause of death listed on the death certificate was pneumonia), as his lungs had gotten so filled with fluid progressively over his final weekend that the doctor making the house call recommended an operation to clear the lungs, and it was on his way to this surgery or treatment that Texano succumbed Though in not-so-great health for many years, Texano took a major turn for the worse after a match on the AAA TripleMania XIII card in May 2005. Soon thereafter, Texano took a bad bump on his back (cascading into many of his vital organs, especially his lungs and ribs), in a cage match in Tijuana, Baja California Norte, a match that turned out to be his last major match. That match featured Texano working with many of his close friends in such veteran luchadores as El Rey Misterio (senior), La Súper Parka (aka El Volador), El Satánico, and El Villano III, an old rival against whom Texano's main bad bump was taken. As noted in an October issue of Box y Lucha, different (feuding) doctors tell different stories, but many believe it was the initial botched surgery to correct the back problems stemming from the cage match that opened up the Pandora's Box of internal wounds from which Texano never recovered. According to Mexican tradition, he was cremated the next day (Tuesday the 17th) before sundown at Mexico City's 'Galloso de Sullivan' Mausoleum. Based on several reports, it appears that El Texano did indeed leave behind three sons, two of whom are wrestlers: El Texano junior (Luis Arturo Aguilar, whom everyone calls 'Arturo'), age 21, and The Dark Spider (his new ring name for 2006, he used to work as The Kempo Kid and The Spider Boy), age 17. The other son is much younger, under 12. He is also survived by his wife, whom Box y Lucha named as Lina Guadalupe Aguilar and whom Ovaciones named as Ana Maria Mendoza Aguilar, and I have no idea yet which name is correct.

Dr. Rafael Rebelin Manríquez, owner of Mexicali's Arena Coliseo (which runs cards every Thursday night), said a benefit show honoring El Texano would be held shortly. Co-organizers are slated to be El Texano's closest wrestling friends in Mexicali - his birth city and capital city of its state - from back in the day: El Principe Negro, El Estudiante, El Negro Azteca, and El Humilde. These final three feuded with Texano when Texano was in AAA in the late 1990s as part of the 'Los Consagrados' team with Sangre Chicana, El Dandy, El Pirata Morgan, and others.

The night of the death, January 16th, at the regular CMLL Monday night show at Arena Puebla before a somber full house of 5,500 fans, many of whom had not heard the news until it was ring-announced, the Mexican tradition of a minute of applause was held for El Texano.

Juan Conrado Aguilar Jáuregui was born on Tuesday, November 26, 1958, in a Cachanilla colonia of Mexicali, the capital city of Baja California Norte, Mexico's northwestern-most state. At the age of 13 years, 2 months, and 6 days, on February 1, 1972, Aguilar had his debut match in the nearby (well, 100 miles, but it is the closest large city) town of San Luis Rio Colorado, in Sonora state, just across the USA border from Yuma, Arizona. Debuting at that age was rare, but not unheard of either - Súper Astro and El Rey Misterio junior debuted in Tijuana at similar ages. For pride-of-place reasons, Texano always had a Western or Cowboy theme to his ring presentation, and on that night, he debuted under a hood as 'Billy the Kid.' Later, he changed his ring name to Roy Navarro, a name taken from his favorite uncle, and trained under Mexicali trainer Caudillo II. From the get-go, Texano was a big success in Tijuana and Mexicali as a young high flier not unlike a Mistico of today, or a Colibri (later Rey Misterio junior) of yesterday. Once or twice, 'Roy Navarro' even appeared on cards in Arena Coliseo from EMLL. EMLL was responding to the UWA 1975 split by heavily pushing younger lighter guys like Fishman, Satoru Sayama, Sangre Chicana, and the like, and was asking regional promoters in Mexico to recommend young fliers. From time to time, he was also billed as 'El Vaquero,' 'Juan El Texano,' or 'Johnny Texas.' But after one of the shows in Mexico City, a very well-respected lucha libre magazine writer named Héctor Valero Maré took Juan aside and suggested 'El Texano' as a ring name instead of 'Roy Navarro' or 'El Vaquero" and Juan agreed.

Many aspiring luchadores of the time, if they aimed for the top and showed promise, spent time in the gym of legendary Guadalajara trainer Cuauhtémoc Velasco Vargas (Diablo Velasco), and El Texano was no exception. In 1976, Texano and several other Mexicali wrestlers such as Zandokan and his brother Huichol, Black Terry, Anfibius, and others, trained days and worked the Guadalajara circuit at nights. He even met his wife there and decided to live there when it was time to raise a family, as it was a very central place to make weekend bookings. Ever the puro cacahanilla, he was now the single Mexicali bloom in central Mexico.

In the mid 1970's, the UWA (more precisely the LLI) of promoter Francisco Flores was in an all-out business war (way, way more intense than the CMLL/AAA battle today) with what had been until recently Mexico's only major wrestling company, the EMLL, still run by its founder Salvador Lutteroth (though not for long, as he soon turned it over to next generation in the family). Flores took note that EMLL was still able to draw with 150-pounders on top despite the fact that he (Flores) headlined Lou Thesz, Canek, Dos Caras, Giant-o Baba, Inoki, etc, i.e., the best heavyweights he could possibly find to headline his main arena, the 'El Toreo de Cuatro Caminos' bull ring in Naucalpan. Flores, no fool he, then cast about for the best young lighter-weight flying talent he could get as well, eventually bringing in foreign gems like 'Ring' Fujinami and 'Samurai Shiro' etc., but also spending a great deal of time watching young Mexican stars whom other promoters had recommended. The first wave of these native young fliers included 'El Brazo De Oro' (Jesús Alvarado Nieves), the oldest son of Shadito Cruz, a low-card worker of the 1950s and 1960s who was considered nonetheless an excellent worker and good trainer, plus two very young, very light fliers who wrestled singles (not tags yet) under the names of 'El Signo' (Antonio Sánchez Rendón) and 'El Negro Navarro' (Miguel Navarro, the 'Negro' in his name meaning evil or black, after 'The Black Shadow,' his idol growing up as a kid).

To illustrate what an impression these youngsters were making, the oldest son of Jose 'Pepe' Casas (today an AAA referee know as Pepe Tropi Casas, but then like Shadito Cruz a low-card worker of the 1960s who was considered nonetheless an excellent worker and a good trainer, and also supposedly the inventor of la magistral) was in training to debut. This son, Jose Casas Ruiz, saw 'El Negro Navarro' (not Thesz, not Canek, not Caras, not Santo, but a 22-year-old little flier) wrestle on Sundays at El Toreo and said 'that's what I want to be like in the ring' and thereafter has called himself 'El Negro Casas.' Indeed, until Casas worked dates for Riki Choshu in 1990s, Casas was a near exact copy of Navarro, with his own style imposed on top of the basic Navarro style, not unlike how Richard Fliehr turned some of himself, some of Ray Stevens, some of Buddy Rogers, etc., into 'Ric Flair.'

Well, back to El Texano. So, here Flores had this super young talent, Signo, Navarro, Texano, El Brazo de Oro, and other Brazo brothers ready to debut, but they just did not have the name or reputation yet of a Fishman or a Sangre Chicana, and by 1977, it appeared that these young guys might get a reputation as permanent low-carders due to very low weight and lack of push. Flores decided to take a risk and programmed a very brief feud leading to a mask match between two of these kids, El Brazo de Oro (born 10-9-1959, so barely 18, and who had only 'officially' debuted October 5, 1977) and El Texano (just now 19).

Not sure the two were ready to work a singles program before anything but smaller crowds, Flores took Shadito Cruz aside and sent them all to shows each Sunday in the fall of 1977 at a gymnasium in Cuahutitlán, a Mexico City suburb. On one of those shows, I do not know which, during November 1977, would wrestle together for the first time as a masked trio together El Brazo de Oro, El Brazo de Plata, and El Brazo, then billed as 'Los Mosqueteros de Diablo.' Also, in that same month and in that same little arena (less than 2000 fans), saw the first time wrestling together of El Signo (born September 4, 1955, debuted in 1973, lost his mask to El Gatúbedo), El Negro Navarro (born October 2, 1955, debuted some time in 1975, never wore a mask), and El Texano, as a trio named 'Los Misioneros de la Muerte.' All six just kids! El Texano and El Brazo de Oro had by all accounts quite a satisfactory program which culminated in El Brazo de Oro's winning the mask of El Texano, which then allowed the Misioneros trio to look more uniform in their ring presence. Thus, on December 4, 1977, El Brazo De Oro won the mask of El Texano in the main event of a show at El Auditorio Municipal Benito Juarez De Cuahutitlán (naturally, in Cuahutitlán city, in the State of Mexico).

Now after this promoter Flores had, instead of 1 or 2 exciting young wrestlers, 2 trios' teams' full. Promoters wanted to book not just one of the guys, but a-team-at-a-time, at a time in Mexico when the wrestling business was much healthier than ever for everyone, with lots of shows the whole country over (aided by the fact that there was no lucha television except strictly local UHF-type stuff and none at all in Mexico City). Why were promoters in Villahermosa and Tijuana and Juarez, etc., asking for the Misioneros? Well, it was due not in small part to the 20-25 weekly lucha magazines, which jumped all over these guys.

For years, other than Box y Lucha, which back then was taken seriously as the weekly bible of lucha libre, the most influential lucha magazine was Lucha Libre, helmed by Valente Pérez. Pérez came up with the gimmicks (and in some cases the wrestlers) for the characters like Mil Mascaras, Dos Caras, Tinieblas, Chicano Power, etc., each of these of which stared as cartoon superheroes in his magazine and after the cartoon gimmick hit, a man was hired to live out the gimmick. To say that Pérez was enamored of big guys, heavyweights, muscles, well that would be a huge understatement. His cartoons were very much paragons of hyper-masculinity. Some were good workers, particularly Dos Caras, but most were slow and awful (legend has it that Superzán, who just recently died, wasn't even allowed to wrestle Arena Mexico after the promoters saw him in the sticks).

Well, when the other, more wrestling-focused lucha magazines, none more respected than El Halcón, saw an obvious trend coming, and saw the fans go goo-goo over the in-ring speed and flashy moves, they hit the ground running, and they made these guys into cover boys and national draws. Fans in Tijuana who saw Los Misioneros on the cover and read the (mostly quite legit) spellbinding tales of their in-ring speed and flair naturally started demanding to see these guys. The few times a year the Misioneros visited these circuits, the trio drew very well. Remember again, this was before anything resembling national TV, and the daily sports newspapers did not yet cover lucha libre (that would come sporadically in the early 1980's and then stay for good after the death of El Santo). However, the three Misioneros all were from vastly different areas of the county (Texano the far northwest, Signo the far Southwest ' Oaxaca state, and Navarro the middle ' Mexico City), and for the next 2-3 years they actually did not work all that terribly often as a trio, certainly not so much as they would from 1980-1986.

By 1980, Signo had won (in Pachuca) the Mexican National Lightweight Championship and, in 1979 in Tijuana against Bobby Lee, the UWA World Welterweight Championship, when that title was one of there 5-6 biggest belts in Mexico and meant something (Flores always promoted championship matches as meaning something, something none of the sons of Salvador Lutteroth ever did). Early on, Signo, with his alpha personality, was considered the leader of the trio. Negro Navarro was, in the locker rooms, considered to be the best worker of the trio, mainly due to his mat skills, a little colorless, but likely to be a huge star with a great ability to carry opponents, and in time possibly even the single best worker in the business. Texano was seen to a certain extent as the third man on the team at the time. To give Texano a bump up and to make the trio team more valuable, Flores had Texano win the UWA World Welterweight Championship at El Toreo on September 7, 1980, from 'El Gringo,' who just three months earlier had relieved Signo of the belt for the purpose of dropping it to Texano.

Now Flores felt things were ready, and the fans would take his new young fast trio team seriously. He started moving them up the cards, and fans kept coming, such that by 1981, they were regularly working main events, and these main events had changed from singles heavyweight matches or four-man tag-team heavyweight-filled matches to trios matches. In order not to be seen as slow or old, the other wrestlers now had to work harder and faster paces, and the increasing the number of wrestlers in a match from 4 to 6 allowed for much more a 'sprint-four-minutes-and-rest-eight-minutes' style. In fact, in some matches with capable opponents, the matches were basically tornado-style, with all men working in or out of the ring for most nearly the entire match, at a furious pace that no one is currently working at today. They also had a cooperative ability to do triple team moves, both giving and receiving, the likes of which simply don't exist today.

Sometime in 1981, the Misioneros were in an El Toreo main event against a trio lead by the ancient (roughly 64-year-old) El Santo, the biggest legend ever in lucha libre and one of the biggest cultural icons ever in Mexico. Signo was in the ring trying to fly around a less-mobile-than-Rufus-R.-Jones Santo when Santo, after taking a blow, collapsed with what would turn out to be a heart attack, the first of 3 or 4 over a less-than-three-year period that ended up killing him. Wrestling being wrestling, you can imagine how this got played up in the magazines ' Los Misioneros were now the team that nearly killed the biggest star and legend of all time. The drawing success of the Misioneros was assured for a few years - and on top too. They all had it good for a while. In reality, though, the old cliché of how the hottest flames burn out fastest would prove itself true in this case, as just four years later, the trio would break up and would virtually never get back together again thereafter.

As a side note, in his final year, El Texano repeatedly (and I do mean repeatedly) said in public that he never got too much more than survival and subsistence wages even during the best of times. Well, wrestling is wrestling.

Nonetheless, the years 1981-1985 were glory years for the trio, fame-wise and lucha-wise. When El Santo came back from his 1981 heart attack, he told Flores that he would work one last sets of bouts in El Toreo (there turned out to be three) as a 'Retirement Tour.' Flores et things up so that El Santo's final-ever match after 40+-years in the ring would be a return revenge match against Los Misioneros. In front of a sell-out crowd of a little over 25,000 fans at El Toreo (which was configured differently then than it is today, so that you could actually seat that many in the bullring) on Sunday, September 12, 1982, 'Los Misioneros de la Muerte' {El Signo, El Texano, and El Negro Navarro} teamed with El Perro Aguayo (senior) to face 'La Pareja Atómica' (El Santo and Gory Guerrero) who teamed with Huracán Ramírez and El Solitario.

By now, the Misioneros, each now weight close to 175 pounds, were major stars. Such light headliners was a major surprise, even more so since they were programmed as rudos and heels against always-larger babyface tecnicos (in lucha libre, usually and to make a really long point in one sentence, the best workers are generally the heels as the style of wrestling in lucha places much more responsibility on the rudos). They had frequent main events at El Toreo including a very famous match on Sunday, April 3rd, 1983, against baby face heavyweights 'Los Tres Caballeros' {El Solitario, Anibal, and El Villano III), who were three of the most legendary luchadores ever, in a match that literally caused a riot of the over 20,000 fans present, when El Solitario, using the Misioneros to turn back rudo against, busted a beer bottle over El Signo's heard and busted him open for the disqualification. Just like 'Los Perros Del Mal' today, the young hard working underdog heel team has that day became the cheered team; they would remain so, whether programmed as rudos or tecnicos, for the next two years.

In fact, they got so hot that were invited to work in the 1980's in Japan, though the Japanese, seeing how very small they were, refused to push them very much at all.

Naturally, when an innovation like this comes along, many wrestlers and promoters are suitable inspired. And, in the UWA, just within the first half of the decade, such 'copycat' or 'inspired' teams as Los Fantasticos (Kung Fú, Kato Kung Lee, and Blackman), Los Temerarios (José Luis Feliciano, Black Terry, and El Lobo Rubio, who also just recently died), El Trio Fantasia (Súper Múñeco, Súper Ratón, Súper Pinochio), Los Cadetes de Espacio (Súper Astro, Solar, and Ultramán), and many others, came to join Los Misioneros and Los Mosqueteros Del Diablo, who were also way over.

In fact, by 1985, some of the above teams had begun to carve into the drawing power of the Misioneros, and it was El Texano himself who saw that the wick on this candle was getting real short. In late 1986, at a card in El Toreo where El Brazo de Oro won the mask of El Indio Rojo on top (I do not know the exact date), the semifinal was a match for the UWA World Trios Championships between 'Las Panteras Rosas' {Los Villanos I, IV, and V) challenging the Misioneros for the belts. During the third fall, El Villano I had El Signo busted open and in a submission hold; it looked as if El Signo was 'going in and out of consciousness,' but he never surrendered. El Texano finally had enough of this and threw in the towel, costing his team the match. When El Signo recovered and found out what happened, he and Navarro attacked Texano and destroyed him (real bad, too, because Texano was headed out of the territory). Texano, having seen the writing on the wall, figured the Misioneros had gone as far as they could, and he gave notice to jump to EMLL, and was working for EMLL full-time by 1987. Once again, the puro cachanilla would be the single Mexicali flower, but now in other promotions, and in 'regular' tag teams.

The Misioneros team was never the same. What Flores did thereafter is now (P.S., just before his death), in hindsight, regarded as most likely the worst mistake he ever made as promoter. He tried to keep the team going with 'lesser' third partners such as El Indómito, Rocky Santana, and Black Power (a great ring name for a white kid from Texas). The fans just completely turned off to this 'lesser substitute' and not only did these new trios fail, but it turns out that the relatively colorless Navarro may well have been killed off by this also. Only Signo, the most charismatic of the three, ever really did well on top, and then not for long ' by 1991, both Signo and Navarro were reduced to working small independent shows for the rest of their careers, living on their reputations.

Not El Texano, though. He moved forward into four-main, as opposed to six-man tags, first with El Dandy, then with Silver King, as 'Los Vaqueros' or 'Los Cowboys' tag teams, and for many years the Cowboys were one of the best tag teams in the world, and likely the best in Mexico. They worked all over the world, for the IWA in Puerto Rico and the IWA in Japan, for WCW (well, one match, and one they were booked to win until the very last moment) as 'The Silver Kings,' for UWA, and for CMLL. The IWA Japan highlight for the duo was a 1995 cage death match against The Head Hunters A and B, in which Texano bled like he never bled before or since. The high spot for 'Los Cowboys' in the UWA came in that promotion's very dying days, as they won a double-hair-versus-double-mask match against 'The Can-Am Express' (Doug Furnas and Phil LaFon) on July 12, 1992, in a match highly considered for match of the year that year in Mexico. And, the duo were also the initial CMLL World Tag Team Champions, winning the tournament to crown the champions in a strange, anticlimactic finals match after a semifinal bloodbath in the same arena between Miguel Perez junior and Ricky Santana vs. Head Hunters had virtually torn Arena Mexico apart and had unintentionally turned Perez and Santana into huge sympathetic faces for the finals match that night.

(P.S. The Misioneros trio did have some matches together after 1985. In 1986, they re-formed to work the CMLL 53rd anniversary show at Arena Mexico and lost their hair in a six-way hair match in a bizarre result to the meaningless team of Americo Rocca, Ringo Mendoza, and Tony Salazar. )

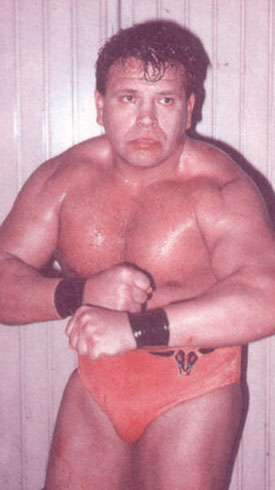

Of course, El Texano worked singles matches, and defended his mask or hair 30 times, winning 18, and was an old-school mat-wrestling-first wrestler who always brought the bull rope and cowbell to the ring with him. He got as large as 5'7' and 210 pounds during the late 1990s ' small for most countries but not for Mexico. He was now working main events with heavyweights. He often felt that he had to work hard to represent Mexico and Mexican wrestling well to other countries and their fans. So, though even as a slower and thicker man in the 1990's he still tried to do huracarranas and topes suicidas as often as possible. Ever the puro cachanilla, Texano now bloomed as the solid veteran all-around worker in the desert of personalities and flash.

He held many title in his career; among them were the Distrito Federal Tag-Team titles with Navarro; UWA World Welterweight, Middlewight, Light-Heavyweight, and Trios titles; WWA (Tijuana promotion) World Tag-Team Titles with Silver King, UWA World Tag-Team Titles with Silver King, CMLL World Tag-Team Titles with Silver King; IWA (Japan) World Tag-Team Titles with Silver King; W*ING/WWC Light Heavyweight Championship; and the Mexican National Tag-Team Titles with El Pirata Morgan. The last title was in AAA, where Texano wrestled for much of the latter half of the decade of the 1990's, either in tags or trios match with Sangre Chicana, Pirata Morgan, and others.

In June 2005, as a result of the match in Tijuana, Texano was no longer the same. He underwent two back operations, for two separate areas of the spine, and by many accounts the surgeries did not go well. Then, the weekend of his death, he caught pneumonia. The date of his death, Texano's still-living grandmother on his mother's side, Magdalena Jáuregui, was told, and she broke down, as her oldest son Bengino Navarro had just passed away on November 2nd in Calexico (in the US).

And is there 'blame' for this death' In a Box y Lucha cover story on the declining health of El Texano, from October 2004, Doctor Antonio Hernández Batista, head of intensive therapy of The Obregón Hospital, said "' He is being supported by ventilator mechanical, his state generally is bad because he has to what we call 'fault ventilatoria par meopatía,' (myopathic trouble breathing) this is weakness in muscles, since he has the problem of which it is not possible to be moved, no longer has capacity to move his diaphragm of an suitable way, then does not breathe well'. The problem is compounded in that without a force sufficient to breathe secretions of mucus in the lungs remain and they become infected; currently, there is a part of his right lung where mucus is 'stuck' and that causes much problem in the interchange of all gases.' the machine keeps him alive but keep generating ancillary dangers. So there is some hope'. Now he is being transferred to The National Institute of Respiratory Diseases. This hospital is between the five first places (one of the 5 best hospitals for respiratory ailments in all of Mexico). Pneumonia that suffers must to that it was long laid down time and that did not have mobility. Hopefully and which all we support at this moment to the Texano since it is at the moment where it must feel solidarity." By November 6, 2004, Texano was back in the intensive care wing of the 'Hospital "Obregón" and his situation was said on Guadalajara TV to be "critical." He would never recover, or even improve.

Quotes from contemporaries:

EL SIGNO: Oh, sure, we had occasional problems, but we always walked together. I believe I spent more time with him than with my own family; and we remained such good friends that now I am here" (literally at the side of his coffin). Asked what he will remember of Texano, he said "the friendship, mainly, and I believe that he leaves some things unfinished. But in the ring he was pure dynamite and that the captainship of the group was really evenly split sometimes me, other times Negro, and in others, him".

EL INDOMITO '(As companions) we traveled often to Monterrey. It became a routine, and just this past December 24th,' he said with tears in his eyes, 'that date, it was necessary very difficult to make the lucha card and still be home for Christmas, but we worked and at the end of the car we had supper without our families, just each other, and we hugged each other, and we did it mutually". Indomito sent a message to Texano's children, "go by the good path, and avoid the many desires thrown at you. Your father taught the finest basics than any child can have. Temptations will arise, but " he said.

MANNY GUZMÁN, ex-leader of the National Union of Fighters, had named Texano president of the Lucha Vigilance Committee from 1990 to 1996, since Texano was were one of the people most serious and respected. "In the ring and out of the ring, I believe that it will be difficult to find another person like him, because what success he had with the Missionaries for eight years! It is a loss rather hard for all of us in lucha libre'.We must support his children through their trials, mainly", he added. "He was a great friend and companion. It is a quite great loss. He was a fighter who had all the qualities. They operated several times, with a knee and a shoulder, remainders (Sims note: taking bone and ligament from other parts of his body to try to replace what was damaged in his back). He was a total package. Unfortunately people think that the free fight is not real, but here the answer to the text is given.'

EL VILLANO III, referring to the Villanos-Misioneros feud: "Those fights were tremendous for us. I do not believe that we shall see again a trio like that one. So well-coordinated and I do not say it because I am an old wrestler always saying the past is better than today, but I have always recognized the uniqueness of the Misioneros and I have said so." He added, "nor were we Los Villanos so perfect a combination as the Missionaries. They united spark, effectiveness and toughness. Thus it is as I knew them. Signo was the spark, the Texano the toughest of the three and with the Negro, everything was spectacular ". He said that some of the bloodiest bout he (El Villano III) ever had were against Los Misioneros, and Villano III was a notorious bleeder. He said that he won the hair of El Texano three times total. He described the trios this way: 'They were an extraordinary trio of rivals, and to me, no current wrestlers, no trio can touch them; today it's different as all members of trios' team wrestle similarly. In Los Misioneros, each had a particular style that complemented the others: Negro Navarro was the fine technician, El Texano had personality, character, and aggressiveness, and El Signo was the born leader who also showed the sparkle. No team today has their coordination or on-mat skills.'

GUADALUPE SANCHEZ: The owner of Suarez of Promotions L.S. in Matamoros Tamaulipas, said that had Texano recovered, Suarez had asked Texano to considering re-forming his team with Dandy in 2006: "I had already spoken with Texano and Dandy, to revive 'Los Cowboys', but sadly, Texano's voice was very slow; he was a noble man, and promoted most that way in the northern circuits. After the herniated disk suffered in Tijuana, doctors operated several times, but without success, and his death was because of debilitative pneumonia. He was so thin! ' Nothing like his old physique, and even worse after the surgeries, especially the first one that semi-paralyzed him. Juan was in a wheelchair long time until already it was impossible to maintain a sitting position and then he remained prostrate in bed.

EL NEGRO NAVARRO: when asked if Texano's injuries are just the price sometimes paid for being a luchador: 'I suppose so. What Texano is suffering is part of the risk of the sporting life, especially lucha libre. I consider Texano to be the best wrestler of the three Misioneros. He was a better mat wrestler, had better delivery, and was more spectacular. El Signo was rougher and more violent. I was kind of a mix of both.'

*** And so we say goodbye to Juan, the single flower that bloomed from Mexicali into a world-wide star, from a family decades and decades in the same Calexican desert, proud, reliable, puro cachanilla'. ***

The song 'Puro Cachanilla,' music and lyrics by Héctor Gasca Reynoso, sung most famously by Vicente Fernandez

Español:

Nací en los algodonales, bajo un sol abrasador; mis manos se encallecieron y me bañé de sudor. Yo soy puro cachanilla, orgulloso y cumplidor.

Mexicali fue mi cuna, Tecate mi adoración; de mi coqueta Tijuana traigo prendido un amor, y por allá en Ensenada se quedó mi corazón.

El cerro del centinela, altivo y viejo guardián, tiene un lugar en la historia de ésta, mi tierra natal. Yo soy puro cachanilla, lo digo sin pretensión: soy de Baja California, norteño de corazón.

Por su valle tan querido mil veces me fui a pasear: Palaco, estación Victoria, Cuervos y mi Mezquital, su gran colonia Carranza, San Felipe y Cucapah.

Mi tierra es una esmeralda, siempre bañada de sol; desde la alta Rumorosa les brindo yo mi canción, a su laguna salada y a toda su gran región.

El cerro del centinela, altivo y viejo guardian.

English:

I was born in the cotton fields, under a burning sun; my hands were callused and I was covered in sweat. I am pure cachanilla, proud and reliable.

Mexicali was my cradle, Tecate I adore, in charming Tijuana I found my first love, and I left my heart in Ensenada.

Sentry hill, the arrogant and old guardian, has a place in the history of this, my native land. I am pure cachanilla, I say without pretension: I am of Baja California, a northerner at heart.

A thousand times I have wished to roams its valley, to see Palaco, Victoria Station, Cuervos, and my Mezquital and its great Carranza colonia, San Felipe and Cucapah.

My earth is an emerald, always bathed in sun! I offer my song from the highest Rumorosa hills to the salty ocean and the whole great region.

Sentry hill, the arrogant and old guardian.

Luchas de apuestas record

Gallery

Punish to Fabuloso Blondy, 1989 |

In Arena Mexico versus Chris Benoit |

In Promo Azteca versus El Zorro |

In AAA punish to Octagon |

In ENESMA versus El Hijo de Anibal |

In LLL putting a chair in Chessman`s head |